Alina Bliumis

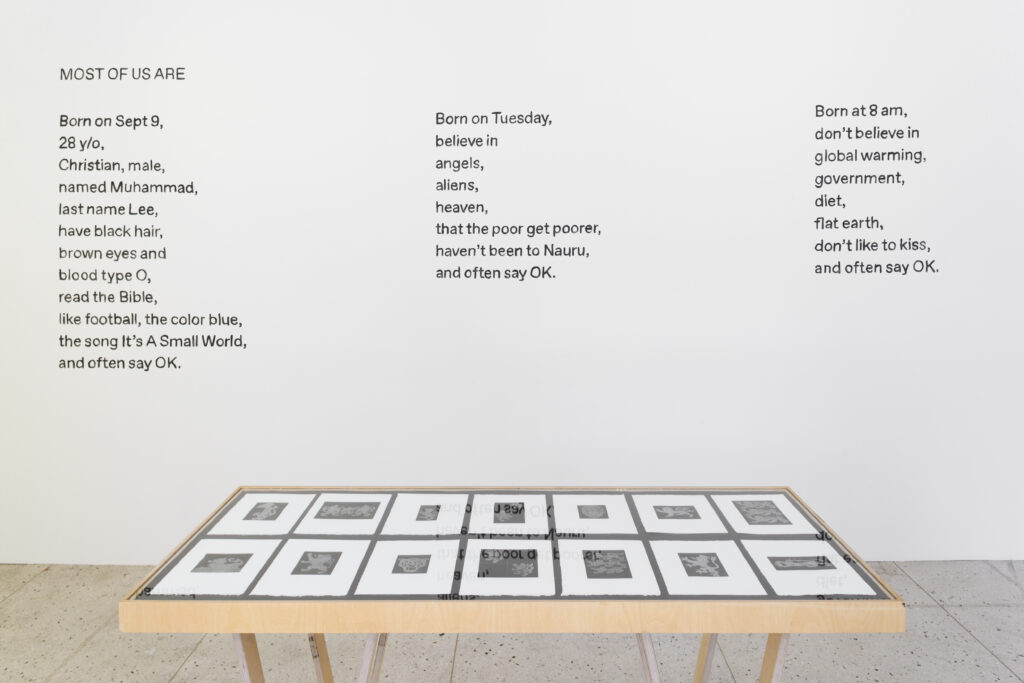

Most of Us Are

2018-2019

How would you describe the average person? What are the things that most of us have in common? What are the characteristics of a global citizen, a trendy term that has become very popular recently? Before the 2020 global pandemic, the world was in the midst of the biggest ever movement of people traveling from their home countries for different reasons ranging from tourism to environmental displacement, visiting relatives to becoming war refugees. More people are identified with being a global citizen than being a citizen of their own country. The pandemic has turned the notion of a “global citizen” on its head, as our movements are now restricted by nationality.

“Most of Us Are” (2018–19) is a series of whimsical poems, presented here as stencils on the gallery walls, that analyses society based on statistics of the most average person worldwide, resulting in a poetic and absurd portrait of the global citizen. In times of social media algorithms, data collection and 23andme, a human is a number, a percentage in biological, psychological, sociological, gender and genetics studies. The world population is summed up in various databases, owned by governments, corporations, universities, online analytics, advisory companies and the media, with some freely available online.

As it turns out, most of us have brown eyes, black hair, are around 28 years old, are born poor yet wish to be wealthy, have a bed, own a TV, believe in aliens but don’t believe in global warming, and don’t like to be kissed.

Classifying, researching, collecting and creating new patterns have been of central concern in Bliumis’s practice. This work in particular is based on statistics demographic research and global opinion polling of recent years. These practices emerged out of the demand for more informed knowledge about international consumer demographics. Bliumis extracted this information from several global polls undertaken recently, including those completed by National Geographic, Wiki, Gallup and the Pew Research Center. Does analysing this data mean that we have a scientific-backed answer to the question of what the global citizen looks, acts like, says or what their dreams are? Bliumis reminds us that in reality, this might look a bit different. “It seems unlikely that all metrics reflect the true reality,” she says.